Inner Voice: The Art of Reading Oneself and Others

Understanding intentions in social interaction Self-awareness and interpersonal communication Psychological development and intentionality Social perception and behavioral interpretation

Inner Voice: The Art of Reading Oneself and Others - by Aleksandar D. - part 1

Many psychological traits are necessary to cooperate with members of your group. Some you acquire through experience, some you develop...

However, none is as important as understanding intentions, whether your own or others'. If you don't understand intentions, even if all your other capacities are above average, social life – whether it's cooperation or competition – will forever remain a mystery.

What do we perceive in contact with other people?

Their behavior, facial expressions, gestures, verbal messages... If it were possible to make a list of such information received during a five-minute conversation, we would probably need a whole day to read it. And the special question is – what and how would we understand.

There are also moments when we see our own behavior in the same way, don't understand our own actions, and later say: "I don't know what got into me to do that!?"

Behaviors, whether individual actions or sets of actions, make no sense until we understand what intention stands behind them.

We understand social interaction in terms of plans, desires, or feelings that lead to certain behaviors. Although you're probably not aware of it, most of the time, we all constantly examine other people's minds, and only some of us get paid for it.

There's no more striking example of this than basketball (which has been the most prominent topic in Serbian media in recent weeks). Five players must cooperate, almost constantly without words, in dozens of offensive and defensive actions.

Many times, at great speed, often in a split second, they must predict what the opponent expects, "sell them a fake" that they'll do one thing and then surprise them by doing the opposite; then regroup and, at full sprint, "read" opponent schemes to predict how not to be deceived.

The same attack or defense type can only be played a few times since a good opponent understands our intentions on the go and changes their behavior.

There's something to athletics, but basketball success is based on the capacity to understand intentions based on movement.

You use the completely opposite principle every time you want to return home alive from driving or walking.

Synchronized traffic is based on making your intentions completely obvious, never changing them without conspicuous announcement, and aligning them with what others, relying on everyone understanding and consistently respecting the rules, will expect from you, and constantly translating their signals and movement into a system of intention.

But, again, it's all about expressing and understanding intentions.

part II

LIMITS OF SELF-KNOWLEDGE

On a less tangible level, we face a great challenge - how to explain ourselves to others. If we want to be truly understood, behavior won't always be sufficient.

This is especially true in situations when we want to impress someone, whether positively or negatively, since then we typically resort to unexpected actions.

But it's difficult to assess how much to say, what to say, how to motivate others to try to understand, and these questions arise both for children and teenagers who feel misunderstood, as well as for adults who are flirting or facing major moral dilemmas.

(To set aside for a moment the question of honesty, despite its enormous importance.)

Countless people have suffered because no one understands them as they would like, so they've turned to alcohol, writing poetry, studying philosophy, lying on couches, and talking about dreams.

A particularly significant problem is that many great friendships and initially happy marriages have fallen apart because after a period of "mutual mind reading," disappointment set in when the other person no longer understands my intentions as I've always wanted and as they could until yesterday.

An additional problem relates to self-knowledge. How can I explain my intentions to another if I'm not sure I understand them well myself? We all face challenges, novelties, crises, when usual forms of behavior and levels of self-understanding aren't sufficient, so we need more self-examination, conversations with friends, or psychotherapy.

As if all that weren't enough, no one doubts anymore that many of our decisions, choices, and behaviors are influenced by unconscious intentions, which we can very difficultly understand and convey to others.

A large part of psychoanalysis is based on examining our possible unconscious intentions to, for example, forget something, which can be completely opposite to those intentions we're conscious of.

Closely related to this is the fact that marketing's purpose is to convince us to buy something by influencing our intentions and plans related to spending money at levels we're not fully conscious of.

conclusion

IN OTHER PEOPLE'S SHOES

Unique challenges arise when we want to understand others' intentions, especially if two people are significantly different (in age, education, gender, cultural background), and we haven't spent enough time interacting, or if the observer lacks sufficient life experience.

There are many sayings about how children still need to learn to understand adult decision-making, how East Asian facial expressions (including their actors) seem insufficiently intense to us while we appear too obvious to them, and the potential misunderstandings between men and women are countless.

A particularly important detail when trying to understand others is that everything here is based on imagination. You feel bodily sensations or emotional processes within yourself, but in others, you imagine everything and can never be certain that you've correctly understood or predicted their intentions.

It's necessary to be extremely careful when assessing someone's inner world and drawing far-reaching conclusions, as it's unclear whether it's easier to make a mistake or express oneself harshly.It's amusing to think of someone saying:

"Here, I'll pay you to imagine what it's like inside me," but this is indeed a good part of psychotherapy work.

There's some solid knowledge, a few general principles, but the main thing is how well I can imagine another person when they were thirty years younger, their parents, the yard where they played, and countless other details I'll never see with my own eyes, and to ask questions and share impressions about all of this.

Therefore, it's especially important for psychotherapists to develop the skill of perceiving and understanding others' internal states, but also the skill to discuss them carefully and cautiously, without the arrogant belief that it's possible for anyone to understand everything.

HIDING INTENTIONS

Finally, this includes the skill of hiding our intentions from others, whether by keeping silent, lying, or leading someone "down the wrong path.

"Sometimes it's clear how we all try to do this (as in the basketball example, or in chess), but often we don't know that we have a deceiver in our team or social group.

This, of course, raises moral questions, which are especially important in contemporary society and postmodern culture in general, where the status of concepts like truth and lies has become extremely diffuse, but it's also a matter of skill and "cold-heartedness."

Shakespeare's Iago is the best and most ominous example of a manipulator who perfectly understands others' intentions, leads them to do everything he wants, destroys the innocent, and refuses to provide any insight into his true intentions.

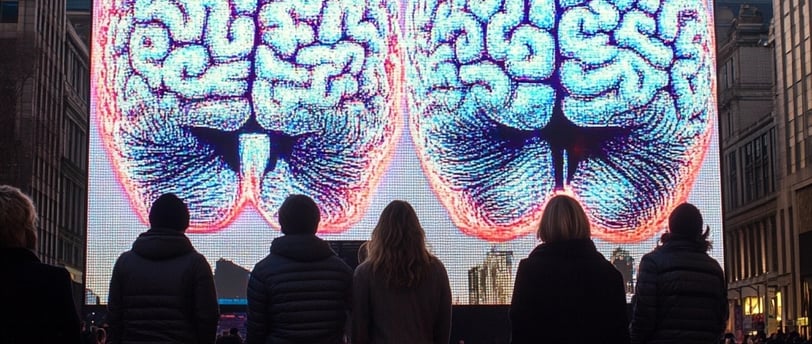

EYES - THE MIRROR OF INTENTIONS

This phenomenon is so important that it's linked to the very beginnings of psychology as an independent scientific discipline.

Even before the establishment of the first psychological laboratories, Franz Brentano proposed founding empirical psychology as a science of intentionality, claiming that the capacity for creating intentions is what distinguishes humans from animals as well as mind from body.

Brentano's students were not only Freud and Husserl but also Franz Kafka, the greatest master of short stories where the boundary between humans and animals is often unclear.

Meanwhile, much effort has been invested in understanding how intentionality develops. Today we know, first, that Brentano wasn't right, since primates and apes can imagine others' perspectives and predict the order in which someone will perform their activities.

And we know that children begin to understand mental phenomena between their fourth and fifth birthdays when they realize their mind is separate from all other minds (that, so to speak, everyone has their own mind) and isn't "transparent" to others' eyes, so they begin to practice having secrets and lying.

We then learn, without anyone explaining it, that we can best perceive others' intentions by following their eye movements.

The majority of information our brains process is visual, so we follow with our eyes what we want, what we fear, where we plan to move, and others can reconstruct this if they carefully observe what we're observing.Finally, we connect with this the expression "madness," both in colloquial and professional sense.

We sometimes use the exclamation "Madness!" for an unexpectedly good joke or completely surprising turn of events – when someone's intention was completely impossible to predict. This meaning comes from our stereotypical understanding of mental disorder as a complete loss of control over mind and behavior,

because of which we imagine – and Hollywood helps us greatly in this – people suffering from it as if there are no intentions behind their behavior, but everything is random and potentially dangerous (one expert expresses his doubt with the words

"Though it be madness, there's method in it"). Fortunately for all of us, this happens to a very small number of people, usually in temporally limited acute states of their disorders, and can dramatically worsen under the influence of alcohol or marijuana (which, also, doesn't apply only to people suffering from mental disorders).

Imagine now how many such operations must be performed by anyone who cooperates with members of any team – from being certain they understand the message content and all terms used, through observing whether something has changed in today's message "tone," to checking whether they understand exactly what's expected of them and assessing whether they should somehow react, and if so, when and how.

The very fact that we are, when needed, able to do all this in a split second speaks to the importance of these processes and our brain's exceptional preparedness for processing information coming from the social world, where intentions come first.The author is a psychologist